The Legacy of Brown v. Board of Education: A Complex Journey of Triumph and Critique

The Landmark Decision and Its Champion

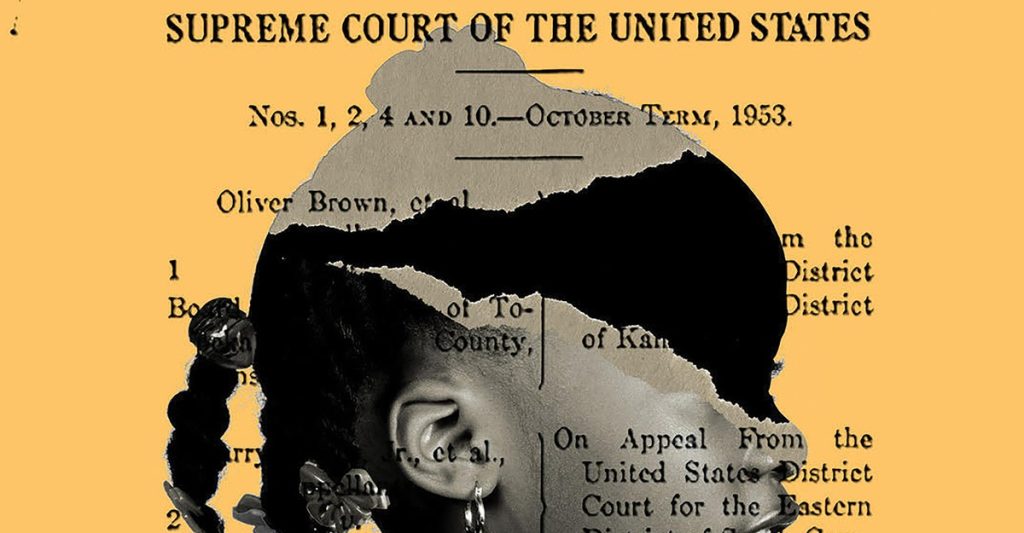

On May 17, 1954, Thurgood Marshall, a 45-year-old lawyer and director of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, sat anxiously in the Supreme Court gallery. Marshall had spent years arguing the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education, a pivotal challenge to the “separate but equal” doctrine that had upheld racial segregation in public schools since the 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson. When Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the Court’s unanimous opinion, declaring that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” Marshall felt a mix of euphoria and numbness. For him, the decision was not just a legal victory but a triumph for the entire Black race, on whose behalf he and his team had toiled tirelessly.

Marshall’s joy was shared by many Black Americans. The Amsterdam News hailed Brown as “the greatest victory for the Negro people since the Emancipation Proclamation,” while civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. invoked the decision to inspire activists nationwide. Oliver Brown, the plaintiff whose name would become synonymous with the case, credited divine providence for the outcome. For years afterward, May 17 was celebrated as a day of liberation and hope. Yet, over time, the decision’s legacy became more complicated, as its promises were tested by the challenges of implementation and the evolving perspectives of Black Americans.

Celebration and Its Meaning for Black Americans

The Brown decision was initially met with widespread celebration in the Black community. Many saw it as a historic milestone, marking the beginning of the end of Jim Crow segregation. Civil rights icon W. E. B. Du Bois, who had dedicated his life to fighting racial inequality, described the ruling as “the impossible happening.” For Black Americans, Brown was more than a legal victory; it was a moral and psychological triumph. It affirmed their humanity and dignity, rejecting the notion that they were inherently inferior. The decision also galvanized the civil rights movement, inspiring activism that would lead to further progress in the years to come.

While the celebration was widespread, not all Black Americans shared the same enthusiasm. Some questioned whether the decision would lead to meaningful change, given the resistance they anticipated from white communities. Others worried about the potential loss of Black schools and the erasure of Black identity in integrated environments. These concerns, however, were largely overshadowed by the optimism of the moment. For many, Brown represented a newfound sense of possibility and hope for a more equitable future.

The Emergence of Early Critiques

As the years passed, the euphoria surrounding Brown began to give way to criticism. By the mid-1960s, some Black leaders began questioning the decision’s impact. Malcolm X, for instance, criticized Brown for its failure to deliver tangible results. He argued that the ruling was a “magical feat” that promised much but offered little in terms of actual desegregation. Malcolm and other critics pointed out that the decision’s implementation was slow and often ineffective, leaving many Black schools still segregated and under-resourced. The phrase “all deliberate speed,” used in the Court’s 1955 follow-up ruling, became a symbol of the delays and obstructions that characterized the desegregation process.

Other critics, such as Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton, authors of Black Power: The Politics of Liberation, challenged the very premise of integration. They argued that the goal of integration was flawed because it assumes that Blackness is inherently inferior. In their view, the focus should not be on integrating Black children into predominantly white schools but on building and strengthening Black communities. They contended that integration often meant assimilation, which undermined Black identity and culture. These critiques marked a shift in the conversation, as some Black Americans began to question whether integration was the most effective path to racial equality.

Modern Critiques: Questioning the Value of Integration

In recent decades, the critique of Brown has gained momentum, with scholars and activists reevaluating its legacy. One prominent critic is Noliwe Rooks, chair of the Africana-studies department at Brown University and author of Integrated: How American Schools Failed Black Children. Rooks contends that Brown should be viewed not as a civil rights triumph but as “an attack on Black schools, politics, and communities.” She argues that the decision led to the closure of many Black schools and the displacement of Black teachers, who had served not only as educators but also as community leaders and activists. These Black educators, Rooks writes, were replaced by white teachers who often failed to understand or support the needs of Black students.

Rooks also draws on her own family’s experiences to illustrate the challenges of integration. Her father, Milton Rooks, excelled in all-Black educational environments but struggled in an integrated law school, where he faced racism and hostility. His experiences, Rooks argues, highlight the emotional and psychological toll that integration could take on Black students. While some Black students thrived in integrated environments, many others faced resentment, marginalization, and trauma. Rooks maintains that the harms experienced by Black students in integrated schools were often overlooked in the rush to celebrate Brown as a victory.

In Defense of Brown: Its Broader Impact

Despite the growing critiques, many scholars and civil rights leaders continue to defend the significance of Brown. They argue that the decision’s importance extends far beyond the classroom. Robert L. Carter, who worked alongside Thurgood Marshall on the Brown case before becoming a federal judge, emphasized that the ruling’s impact was not limited to education. Brown fundamentally reshaped the psychological and legal landscape of race relations in America. It struck a blow to the legitimacy of segregation and provided a legal foundation for the broader civil rights movement. Carter noted that before Brown, Black Americans often felt compelled to plead for equal treatment; after the decision, they could demand it as a right.

The decision also inspired a wave of activism that led to landmark legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. For many, Brown represented a moral reckoning with the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow, a declaration that segregation was inherently unjust. While the decision’s implementation was imperfect and often slow, its symbolic power was undeniable. As Nelson B. Rivers III, a South Carolina NAACP official, once said, any romantic nostalgia for segregation ignores its brutal realities.

Conclusion: The Complex Legacy of Brown

Seventy years after the Brown decision, its legacy remains fraught with complexity. While it marked a turning point in the fight against segregation, the realities of its implementation were often disappointing. The decision’s promise of equality was undermined by resistance from local governments, the vagueness of “all deliberate speed,” and the persistence of systemic racism. For many Black Americans, the closure of Black schools and the displacement of Black teachers were profound losses that went unacknowledged in celebrations of Brown as a civil rights triumph.

Yet, to dismiss Brown as a failure overlooks its broader significance. The decision’s attack on segregation emboldened a generation of activists and inspired a racial revolution that transformed American public life. While integration has not always achieved its intended outcomes, the critique of Brown often idealizes a past that was marked by inequality and injustice. The story of Brown is one of both triumph and frustration, a reminder of the ongoing struggle for racial equality and the enduring need for systemic change. Its legacy challenges us to reflect on the meanings of justice, community, and education in a society still grappling with the remnants of segregation.