The Trade Deficit Is Not Made in America: A Global Perspective

Introduction: Rethinking the Narrative on Trade Deficits

For decades, American policymakers have been fed a simplistic narrative about trade deficits: the United States runs persistent deficits because it doesn’t save enough. The argument goes that if Americans were more frugal and the federal government controlled its spending, the trade deficit would shrink, and manufacturing jobs would return. This view, recently echoed by economist Maurice Obstfeld in the Financial Times, suggests that the solution to the trade deficit lies entirely within U.S. borders. However, this narrative ignores a critical reality: the U.S. trade deficit is not just a domestic issue but is driven by foreign economic policies designed to suppress consumption abroad and flood the U.S. with excess savings. The real story of trade imbalances is far more complex and global in nature.

The Real Cause of Trade Imbalances: A Global Problem

The conventional wisdom that the U.S. runs a trade deficit because Americans spend more than they produce oversimplifies the issue. While it is true that the U.S. consumes more than it produces, this is not the root cause of the problem. Instead, the persistent trade deficit is driven by deliberate policies in countries like China, Germany, and Japan, which suppress wages, limit domestic consumption, and push excess savings into the global economy. These nations engineer their economies to produce far more than they consume, creating massive trade surpluses. The excess savings from these countries do not stay within their borders; they flow outward, seeking a destination. The United States, with its open capital markets, becomes the primary absorber of these surpluses, leading to a larger trade deficit. The problem, therefore, is not American profligacy but the artificial economic policies of foreign governments.

Foreign Economic Policies: The Unsaid Story

The role of foreign governments in shaping global trade imbalances is the most overlooked aspect of the trade deficit debate. China, for instance, enforces high savings rates by suppressing wages, limiting household wealth, and directing cheap credit to state-owned enterprises rather than consumers. These policies create excess savings that do not stay in China. Instead, they flow into global markets, where they find their way into the U.S. due to its open capital markets. As economist Michael Pettis explains, when China accumulates massive surpluses, they have to be absorbed somewhere—and that means an automatic increase in the U.S. trade deficit. The persistence of these deficits, which have been a feature of the U.S. economy since the 1970s, suggests that something more systemic is at play. The scale of the imbalance is staggering: the U.S. ended 2024 with a goods trade deficit of approximately $1.2 trillion, and the December 2024 trade deficit alone was $98.43 billion. If this were simply about inadequate U.S. savings, we would have seen these deficits fluctuate significantly over the years. Instead, their persistence suggests foreign mercantilist policies that rig the global system in their favor.

The Flawed Assumption: Why Tariffs Are a Necessary Response

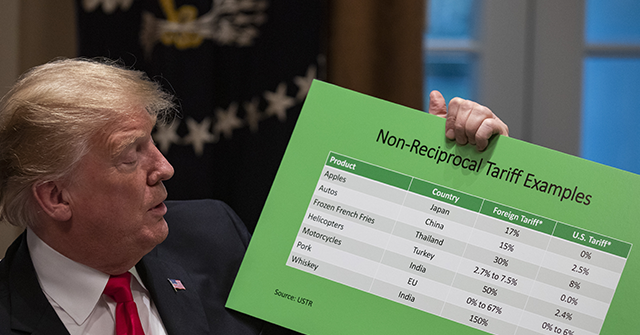

If the U.S. trade deficit is being imposed by foreign intervention rather than American choices, then tariffs are not just an economic tool—they are a defensive measure. The Trump administration’s tariffs on China, Mexico, and Canada are part of a broader strategy to force surplus nations to stop distorting global trade and capital flows. Obstfeld dismisses tariffs as ineffective, arguing that they won’t shrink the trade deficit or bring back manufacturing. But this assumes that tariffs operate in a vacuum. In reality, tariffs are one piece of a broader effort to counter foreign economic distortions. Without them, the U.S. is simply allowing itself to be the dumping ground for other countries’ surplus production. Take China’s economy, for example. Its massive trade surplus isn’t the result of natural free-market forces—it’s the direct result of Beijing’s industrial policies, state-controlled banking system, and currency interventions. The only way to change this is to make China feel the cost of its own policies. Tariffs increase that cost. They force China to reconsider whether its strategy of suppressing consumption and flooding the U.S. with cheap goods is sustainable.

The Broader Issue: America’s Economic Sovereignty

The core issue here isn’t just trade deficits—it’s America’s economic sovereignty. For decades, the U.S. has let foreign nations dictate its economic reality. We allowed China to become the world’s factory, gutting our industrial base. We accepted trade deficits as an unavoidable consequence of globalization. And we let foreign capital distort our financial system, fueling bubbles and debt-driven growth. Trump’s tariffs challenge this status quo. They are a recognition that America cannot fix its economy without confronting the policies of surplus nations that have spent decades rigging the system in their favor. Obstfeld’s solution—cutting U.S. spending and increasing savings—ignores the fact that America cannot out-save an economy like China’s, where savings rates are artificially inflated by government intervention. It would also involve far more economic intervention than simply addressing the trade imbalance head-on.

Rebuilding American Economic Sovereignty: A Path Forward

The real solution is to reshape global trade and capital flows so that the U.S. economy is no longer at the mercy of foreign mercantilism. As a first step, that means tariffs and the kind of conservative industrial policy of tax cuts and deregulation that Trump has advocated. It means rejecting the idea that America’s economic fate is solely determined by domestic policy decisions. And it means recognizing that in a world where other nations play by different rules, America has every right to protect itself. The U.S. trade deficit is not just a number on a balance sheet; it’s a symptom of a deeper problem—a global economic system rigged against American workers and businesses. To fix it, the U.S. must take a stand and assert its economic sovereignty on the world stage.