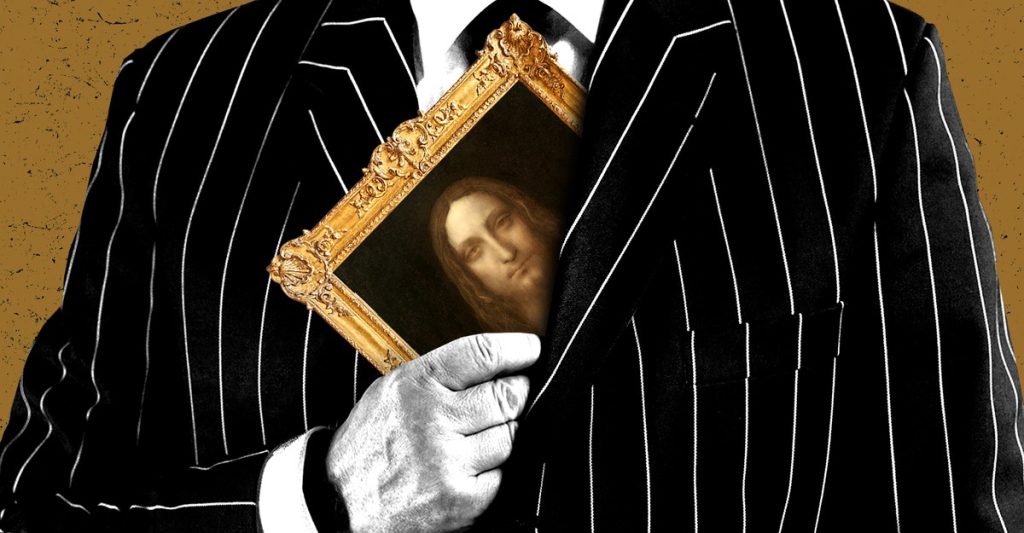

The journey of the Salvator Mundi, a painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, serves as a metaphor for the evolving role of the ultra-wealthy in society. Commissioned in the early 1500s, the painting reflects the historical tradition of wealthy patrons supporting the arts as a form of social responsibility. Over the centuries, the Salvator Mundi changed hands numerous times, often owned by royals and nobles who used it to symbolize their status and philanthropy. However, its modern trajectory, particularly after its record-breaking sale to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman for $450.3 million, highlights a shift from public spiritedness to private opulence.

The Salvator Mundi’s odyssey is emblematic of how today’s elite have moved away from the classical model of patronage, where the wealthy invested in public goods and cultural projects to benefit society. In the past, the likes of the Medici family in Florence used their wealth to fund cathedrals, public spaces, and artworks, not only for personal glory but also to fulfill a social contract. This social contract, emerging after the Black Death, tied wealth inequality to the obligation of the rich to contribute to the common good.

Today, the ultra-wealthy often leverage their resources to enhance their personal lifestyles and status within their elite circles. Instead of commissioning cathedrals or funding public projects, they invest in private yachts, exclusive art collections, and luxury real estate. The Salvator Mundi, now displayed on Crown Prince bin Salman’s superyacht, Serene, symbolizes this shift. Instead of being a shared cultural treasure, it is a private luxury item, inaccessible to the public and serving only the indulgence of its owner and select guests.

This transformation reflects a broader societal change where the wealthy increasingly disengage from social responsibility. During the COVID-19 pandemic, while millions faced economic hardship, the rich found solace in their private yachts, jets, and virtual Writing about David Geffen’s isolation on his superyacht during the pandemic underscores this disconnect. The notion of “munificence” – the belief that generosity is optional rather than obligatory – has replaced the historical “public theology of magnificence,” where the wealthy were expected to contribute to society’s well-being.

Despite some exceptions, such as Bill Gates’ philanthropic efforts in global health, the overall trend among the ultrarich leans toward self-interest. The normalization of tax evasion, shell companies, and luxury spending signals a departure from the civic responsibilities that once accompanied great wealth. This erosion of social responsibility is not merely a moral issue but a symptom of a disintegrating social contract, where the ultrarich no longer feel bound to contribute to the public good.

In conclusion, the Salvator Mundi’s journey from a symbol of religious devotion and public art to a private trophy on a superyacht encapsulates the transformation of the ultrarich’s role in society. The shift from shared social responsibility to self-indulgence not only widens the chasm between the rich and the poor but also undermines the cultural and social fabric that once connected them. As the wealthy increasingly seek to escape into their private worlds of luxury, the notion of a shared society becomes ever more tenuous.