"Brother Brontë": A Wilderness of Words and Worlds

A Book that Refuses to Be Contained

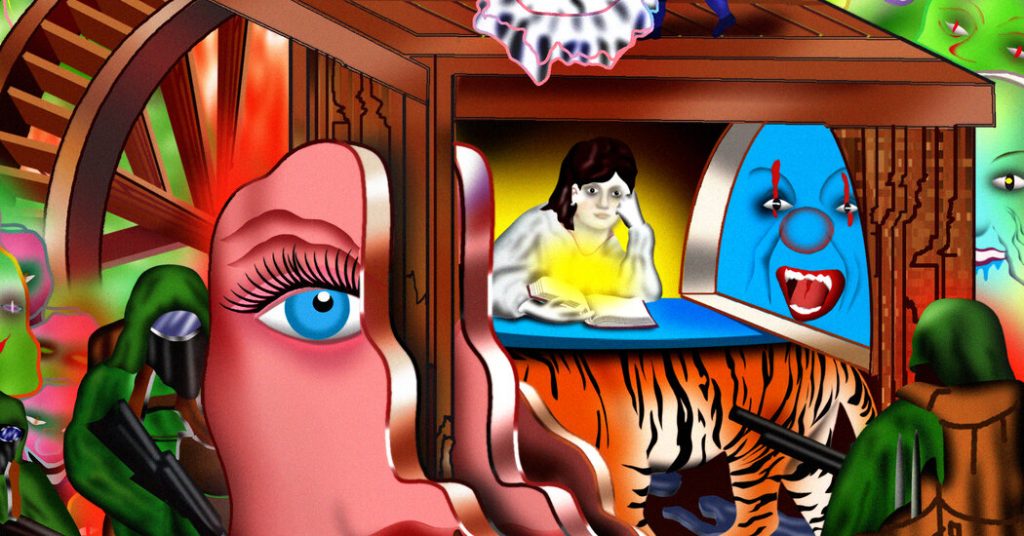

"Brother Brontë," the latest offering from Fernando A. Flores, is less of a novel and more of an experience—a sprawling, kaleidoscopic feast that defies easy categorization. It is a book that overflows with ideas, imagery, and invention, a literary equivalent of that mythical sub sandwich "with literally everything on it." Open its pages, and you are thrust into a world that is as fantastical as it is unpredictable. Flores writes with a abandon that is both exhilarating and exhausting, throwing everything into the mix: tangential detours into Jazzmin Monelle’s other novels, plays like "Great Headwounds in Underground Art Movements," and even a magical tiger that could have stepped out of a Bollywood extravaganza. The prose is sumptuous, volatile, and gloriously anarchic, levitating off the page with lines like, "Turmeric-colored mist had hidden wheels and levers operated by giddy, sadistic gnomes," or "Silence. The keys of a piano, ascending like a spiral staircase within the bare bones of a blood-filled mountain." This is not a book for the abstemious reader. It is an all-you-can-eat buffet of language, a riot of invention that demands to be devoured.

A Surreal Landscape of Dreams and Nightmares

At the heart of "Brother Brontë" is a sense of the oneiric and the phantasmagorical. Flores’ world is a Bosch-like Bosch meets Brecht, where the surreal and the dialectical coexist in a delicate tension. The novel is full of eschatological longing, a yearning for some last intimacy with a world that seems on the brink of destruction. "Brother Brontë" is a book that asks questions about the right to poetry, the right to live poetically, in a world that seems increasingly hostile to such naive aspirations. And yet, in that very naivety, there is something insurrectionary, something revolutionary. Flores is not a polemical writer, but he is asking us to consider: can we afford to be naive in these dark times? Can we still cling to the idea that poetry—and the living of a poetic life—is an inalienable right?

A Resistance in Print

One of the most striking aspects of "Brother Brontë" is its portrayal of the criminalization of book possession, the idea of reading as a transgression. In a world where consumer goods are scarce and black markets thrive for every conceivable item, the possession of a book becomes an act of defiance, a refusal to surrender to the forces of oppression. Flores seems to suggest that literature itself is a form of resistance, a way to keep hope alive in a dying world. The novel is rambunctiously lyrical, gloriously evangelical about literature, and unapologetically passionate about the power of words. It is a book that makes you want to read more, to write more, to believe in the transformative power of language.

A cornucopia of Influences and Allusions

"Brother Brontë" is a novel that wears its influences on its sleeve, but with a sui generis originality that is rare in contemporary literature. There are echoes of Borges in the blind director of the Biblioteca Nacional de Buenos Aires, who uses a red rose and a mirror to save a distant dying planet, Zapotec, from destruction. There are Shakespearean identity switches, assassinations, and black markets for everything from consumer goods to ideas. Flores’ prose is infused with the spirit of Jazzmon Monelle’s other works, such as "I Was a Teenage Brain Parasite" (one of those titles that makes you wish you’d come up with it yourself) and "Ghosts in the Zapotec Sphericals." These influences are not mere pastiche; they are transformed and reimagined in the furnace of Flores’ imagination, emerging as something entirely new.

A Triumph of Style and Substance

At its core, "Brother Brontë" is a triumph of both style and substance. Flores’ prose is not just pyrotechnic; it is precise, evocative, and deeply moving. The novel is full of moments that make you stop and reread a sentence, not because it is obscure, but because it is so vivid, so alive. Take, for example, the line, "Her head felt like it was a tiny head trying to break out of a larger, more oppressive head, and her stomach held smoldering cinders." This is prose that does not just describe; it conjures, it evokes, it inhabits the reader. Flores has a gift for creating images that linger in the mind long after you’ve turned the page.

A Call to Arms for the Power of Literature

Ultimately, "Brother Brontë" is a book that needs to be read, not just for its inventiveness, its lyricism, or its ambition, but for its unshakable belief in the power of literature to transform and transcend. In a world that often seems hostile to the very idea of poetry, Flores reminds us that to write, to read, and to live poetically is an act of resistance, an act of hope. "Brother Brontë" is not just a novel; it is a manifesto, a declaration of faith in the power of words to change the world. As Flores himself might say, losing this world might be our only hope for some last intimacy with it. And so, we read, we write, we resist. Bravo, Brother Brontë. Bravo, Fernando A. Flores.