A Life of Artistic Integrity: Hal Hirshorn (1965-2025)

Hal Hirshorn, a beloved figure in New York City’s vibrant artistic landscape, passed away on February 4, 2025, at the age of 60 due to coronary artery disease. His death occurred at a friend’s Manhattan apartment, where he had gathered to celebrate the opening of a group exhibition, “Let There Be Light,” at the Church of the Heavenly Rest. Hirshorn was an artist known for his unique approach to art, which stood apart from the city’s fast-paced commercial art scene. Using antique cameras and homemade paints, he created haunting photographs and landscape paintings that captured a timeless essence, earning him a reputation as an avatar for living a creative life unfettered by financial pressures.

Despite the overwhelming commercialism of New York’s art world, Hirshorn remained true to his artistic vision, rarely selling his work through galleries. His sparse website offered a glimpse into his portfolio but revealed little about his personal life. His dedication to analog techniques was unwavering; he crafted his own paints from traditional ingredients and scoured flea markets for obscure camera parts. This commitment to tradition resulted in landscapes that were both Turner-esque and abstract, with swirling mists and stormy seas rendered in muted tones of green and brown. His photographs, made using a 19th-century salt-and-silver process, were equally distinctive, often depicting women in ethereal or domestic settings. Hirshorn’s art was a testament to his ability to bridge the past and present, creating works that felt both nostalgic and contemporary.

A Passion for Process: Hirshorn’s Artistic Techniques

Hal Hirshorn’s artistic process was as unique as the man himself. He was deeply committed to analog methods, rejecting the digital revolution that had transformed the art world. His landscapes were painted with homemade pigments, meticulously crafted to achieve a specific texture and color palette. His photographs were created using a salt-and-silver process, a technique that required long exposures and often resulted in hazy, otherworldly images. This blurriness was not a flaw but a deliberate choice, adding an ethereal quality to his work. Hirshorn’s subjects were equally evocative, ranging from women engaged in domestic chores to “memento mori,” a 19th-century photography tradition he adapted using live models. His attention to detail was meticulous, as he sometimes applied makeup to his models’ feet to enhance the authenticity of their appearance.

One of Hirshorn’s most ambitious projects was a 2011 “funeral” for Seabury Tredwell, a wealthy Manhattanite who had died in 1865. Hirshorn staged a procession from the Merchant’s House Museum to Grace Church and finally to the New York City Marble Cemetery, capturing the event with his salt-print camera. This project typified his approach to art, blending historical references with a deeply personal and contemporary sensibility. His work was not merely an homage to the past but a reinterpretation of it, infused with his own unique perspective. As photographer and close friend Geoffrey Berliner noted, Hirshorn’s art was a seamless blend of 19th-century influences and modern subjectivity.

An Enigmatic Presence: Hirshorn’s Personality and Lifestyle

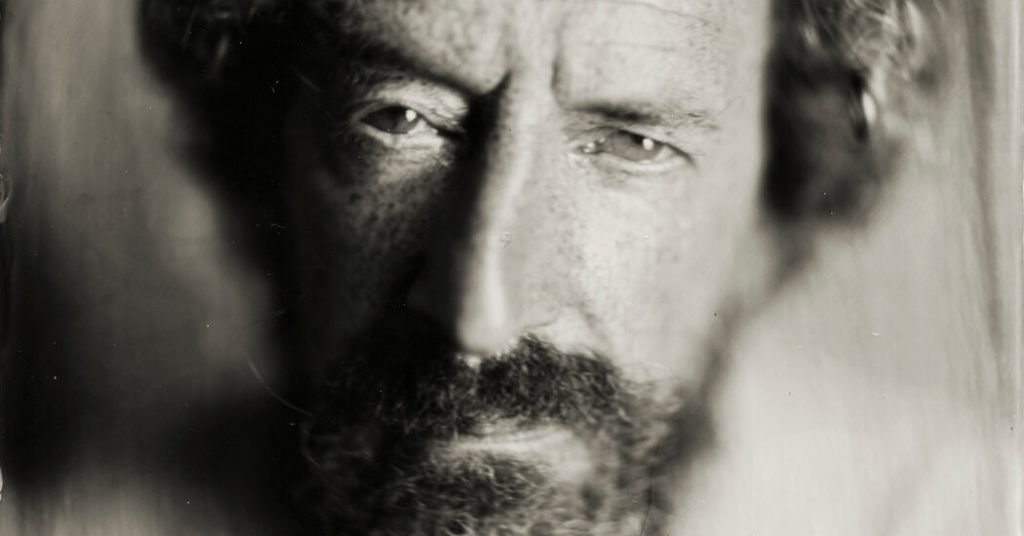

Hal Hirshorn’s personality was as fascinating as his art. He was an enigmatic figure, with a sparse LinkedIn profile that described him as an “artist at everything and nothing.” This cryptic description aptly captured his essence; he was a man who defied easy categorization. His friends and admirers frequently encountered him at museums, gallery openings, and even random sidewalks and parks, giving rise to the nickname “Zelig-like,” a reference to the Woody Allen character who seemed to be everywhere at once. Hirshorn’s appearance was equally striking, with his pale face, mop of curls, and piercing eyes. His slow, measured movements, punctuated by sudden sprints, added to his air of mystery.

Despite his ubiquity, Hirshorn maintained a sense of privacy. He lived in a small, rent-controlled studio apartment off Washington Square Park, filled to the brim with camera parts, books, and artistic ephemera. The space was sparse, with a hot plate and a shared bathroom, but it was home to a man who had little interest in material possessions. Hirshorn’s focus was on his art, and he lived a life that was as much about his inner creative dialogue as it was about external validation. As artist Tom Sachs, a friend from college, observed, Hirshorn’s art was a deeply personal expression, driven by a commitment to his craft rather than fame or influence.

A Life Shaped by Art and History: Hirshorn’s Background

Hal Hirshorn’s journey as an artist began early, shaped by his peripatetic childhood and a family deeply rooted in art and history. He was born on January 12, 1965, in Philadelphia to Bruce Hirshorn, a Foreign Service officer, and Anne Sue (Friedberg) Hirshorn, an art historian. His childhood was spent in various cities, including Brussels, London, and Hong Kong, before his family settled in Washington after his parents divorced when he was 9. Hirshorn often credited his mother with instilling in him a love for art, which would become the defining force of his life. After attending Bennington College, where he studied art history and architecture, Hirshorn moved to New York in 1989, just as the city’s art boom was beginning to wane. He settled in the East Village, where he found a small, affordable studio that would be his home for the rest of his life.

Hirshorn’s artistic journey took him through various mediums and influences, but his work remained consistently rooted in the past. From the sepia-toned photographs of women scrubbing floors to the eerie, time-capsule quality of his memento mori series, Hirshorn’s art was a constant dialogue with history. His 2011 funeral procession project, reimagining the burial of Seabury Tredwell, was a testament to his fascination with the 19th century. Even in his final project, a photographic series documenting the restoration of a historic African American cemetery in Midland, Georgia, Hirshorn’s work was about bridging the gap between past and present. Though he did not live to develop the negatives from this project, his friend Jeremy Hutchins has vowed to complete it, ensuring that Hirshorn’s artistic legacy endures.

Leaving a Lasting Legacy: Remembering Hal Hirshorn

Hal Hirshorn’s passing has left a void in New York’s artistic community, but his work and spirit continue to inspire those who knew him. His funeral procession project is a fitting metaphor for his life’s work, which was always about creating a sense of continuity between the past and the present. Hirshorn’s art was a testament to the power of tradition and the importance of preserving historical techniques in a rapidly changing world. As his friend Geoffrey Berliner noted, Hirshorn’s ability to reinterpret the past in personal and contemporary ways was his greatest strength.

In the months following his death, Hirshorn’s work will be celebrated in an exhibition at the Ethan Cohen Gallery in Chelsea, showcasing not only his art but also his vast collection of antique cameras. This exhibition promises to introduce his work to a new audience, ensuring that his unique vision continues to inspire future generations of artists. Hirshorn’s life was a testament to the enduring power of art to transform and transcend. He may have lived outside the mainstream, but his work was never about being outside—it was about being deeply connected to the art and history that shaped him.

Hal Hirshorn, as friend James Harney once observed, had an almost Edwardian air about him, but he also had a playful, Zelig-like quality that made him impossible to miss. He was a man of paradoxes, a 21st-century artist with a 19th-century soul, and it is this duality that will be remembered as his greatest legacy.