Athol Fugard: The Chronicler of South Africa’s Apartheid Past and a Beacon of Shared Humanity (Heading 1)

In early 2010, the author found themselves in a Cape Town coffee shop, where they encountered a bearded man who looked familiar. It turned out to be Athol Fugard, South Africa’s most celebrated playwright and a chronicler of the country’s apartheid past. Fugard, who passed away in late 2023, was both an ordinary and extraordinary individual. His enthusiasm for people and their potential was matched by his unflinching willingness to confront the darker aspects of human nature, both in others and himself. This duality was reflected in his work, where he often drew from his own life experiences, including the infamous scene in "‘Master Harold’ … and the Boys," in which the young white protagonist spits in the face of his Black mentor. This moment, Fugard admitted, was inspired by his own past, showcasing his ability to confront uncomfortable truths.

Fugard’s writing was known for its moral clarity, achieved by delving into the intimate, often painful details of his characters’ lives. As noted by theater critic Frank Rich in a 1982 New York Times review, Fugard’s technique was to uncover moral imperatives by burrowing deeply into the fallible lives of his characters. His plays were not just critiques of apartheid but also explorations of the human condition, offering a profound examination of race, identity, and morality.

The Power of Fugard’s Plays: Unflinching Truth and Deep Humanity (Heading 2)

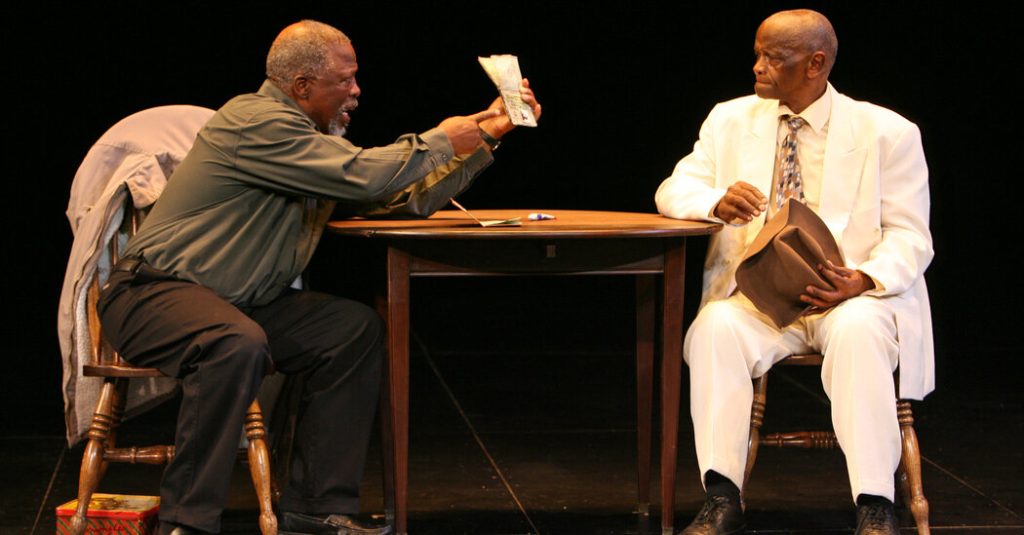

The author’s first encounter with Fugard’s work was in the early 1980s, during a production of "Sizwe Banzi Is Dead," a play co-written with Winston Ntshona and John Kani. The story of a man who assumes another identity to gain a coveted passbook was both bleakly comic and deeply unsettling. For someone who grew up in apartheid South Africa, the play was a visceral reminder of the dehumanizing reality of passbooks, police raids, and the systemic cruelty of the regime. Yet, Fugard’s writing also brought a humanity and warmth to the characters, making the cruelty of apartheid even more excruciating to witness.

Fugard’s most famous works—"Blood Knot," "Boesman and Lena," "The Island," "The Road to Mecca," "Sizwe Banzi," and "‘Master Harold’ … and the Boys"—are unsparing in their portrayal of how race determined relationships under apartheid. They expose the moral blindness perpetuated by the regime while offering a deeply humane perspective on the lives of those affected. As producer and philanthropist Eric Abraham noted after Fugard’s death, his plays were a call to confront the past and learn from it. Fugard believed that divisions could only be overcome by recognizing a shared humanity, a message that resonates just as strongly today.

Fugard’s Legacy: A Theater Named After Him and the Ghosts of the Past (Heading 3)

In 2010, Fugard was in Cape Town rehearsing his new play, "The Train Driver," which would premiere at the Fugard Theater, named in his honor. Located in District Six, a historically mixed-race neighborhood declared “whites only” in 1966, the theater became a vibrant cultural beacon in South Africa. Fugard often spoke of the ghosts of the past that lingered in the area, referencing the lives of those who had been displaced and forgotten. On opening night, he said, “You will be sitting in the laps of the ghosts of the people who couldn’t be here,” acknowledging the weight of history that the theater represented. Tragically, the Fugard Theater closed in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a poignant reminder of how fragile cultural institutions can be.

The theater was not just a physical space but a testament to Fugard’s enduring influence. Over the years, it hosted numerous productions of his plays, ensuring that his work remained alive and relevant. Fugard’s plays were always about bearing witness to forgotten lives and confronting the moral blindness of apartheid. They were a reminder of the past, but also a call to action for the present.

A Man of Contrasts: Fugard’s Humility and Intensity (Heading 4)

Despite his prominence, Fugard remained unpretentious and humble. The author met and interviewed him several times over the years, finding him to be intense yet jovial, always eager to engage in conversation. Fugard often referred to himself as an “outsider artist,” someone without formal training or a degree, who began writing at a time when South African stories were not considered worthwhile for the stage. Yet, by staying rooted in his local context, he transcended borders, creating work that spoke to universal themes.

Fugard’s home life reflected his down-to-earth nature. After the Fugard Theater opened, he returned to South Africa, settling first in New Bethesda, the setting of his play "The Road to Mecca," and later in Stellenbosch with his wife, Paula Fourie. These places inspired him, and he continued to write, driven by his passion for storytelling. His invitation to “come over for a glass of wine” at the end of an interview was emblematic of his warmth and hospitality—a quality that made him beloved by many.

The Timeless Relevance of Fugard’s Work (Heading 5)

Fugard’s plays were not just products of their time; they remain relevant today, offering insights into the human condition and the enduring impact of systemic oppression. His work continues to challenge audiences to confront uncomfortable truths about race, identity, and morality. As Abraham wrote, Fugard’s plays urged people to rifles through the boxes of their past, not to dwell on it, but to learn from it and move forward. His belief in the power of shared humanity was a beacon of hope in a world often divided by prejudice and hostility.

In a world that still grapples with issues of race and inequality, Fugard’s work serves as a reminder of the importance of empathy and understanding. His commitment to storytelling as a tool for moral clarity and social change ensures that his legacy will endure long after his passing. As we reflect on his life and work, we are reminded of the profound impact one person can have on the world.

A Final Toast to Athol Fugard: A Life of Purpose and Passion (Heading 6)

Looking back, the author wishes they had taken Fugard up on his invitation for a glass of wine. It would have been an opportunity to experience firsthand the warmth and generosity that defined him. But even without that moment, Fugard’s work and legacy continue to inspire and challenge us. His plays are a testament to his belief in the transformative power of theater and the importance of confronting the past.

Athol Fugard leaves behind a body of work that is both a chronicle of South Africa’s apartheid era and a universal exploration of the human condition. His passing is a loss not just for South Africa but for the world. Yet, his plays remain, offering us a way to grapple with the complexities of our shared humanity. As we remember him, let us also honor his legacy by continuing to engage with the questions he posed and the truths he uncovered. In doing so, we ensure that his voice continues to resonate, guiding us toward a more compassionate and inclusive future.